This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #70, on the subject of Writing Backwards and Forwards.

When I was at TheExaminer, I eventually took to creating indices of articles previously published; when I moved everything here last summer, I included those indices, and finished one that covered the first half of 2015 (through July). On the last day of December I did a review piece indexing the rest of that year, as #34: Happy Old Year.

It may seem premature to do another index; it is not even falling on a logical date (although as I write this I am not completely certain on which day it is going to be published). However, some new “static” pages have made it to the web site, and quite a few more web log entries, and it seems to be a time of decision concerning what lies ahead. Thus this post will take a look at everything that has been published so far this year, and give some consideration to options going forward. You might find the informal index helpful; I do hope that you will read the latter part about the future of the site.

Temporal Anomalies/Time Travel

The most popular part of the web site is probably still the temporal anomalies pages. It certainly stimulates the most mail, and the five web log posts (including those in the previous index) addressing temporal issues received 30% of the blog post traffic. We added one static page since then, a temporal analysis of the movie 41. We also added post #56: Temporal Observations on the book Outlander, briefly considering its time travel elements of the first book in the series that has made it to cable television. We’d like to do more movies, and there are movies out there, but the budget at present does not pay for video copies.

This part of the site has been recognized oft by others (before it was a Sci-Fi Weekly Site of the Week it was an Event Horizon Hotspot), and the latest to do so is the new Time Travel Nexus, a promising effort to create a hub for all things time-travel related; we wish them well, and thank them for including links to our efforts here. They recently invited me to write time travel articles for them, although if I do it will have to be something different, and we have not yet determined quite what.

Legal/Political

By sheer number of posts, this is the biggest section of the web log. Although since the last of these indexing posts it has been running even with posts about writing and fiction, it has a significant head start, with half of the articles in that index connected to law or politics primarily. Some of these have religious or theological connections as well–that can’t be helped, as even the First Amendment in the Bill of Rights recognizes that the protection of your right to believe what you wish, express that belief, and gather with others who share that belief is both a religious and a political right, and cannot always be distinguished. (Anyone who says that religion and politics should always be kept separate misses this critical point, that they are really the same thing. It’s a bit like saying that philosophy and theology should be kept separate–the difference is not whether God is involved, but how much emphasis is placed on Him. So, too, politics is about religious beliefs in application.)

Trying to sort these into sub-categories is difficult. Several had to do with legal regulation of health care, several with discrimination, and we had articles on freedom of expression, government and constitutional issues, election matters. These twenty-seven articles together drew 35% of readers to the web log, but a substantial part of that–13%–went to the two articles about the X-Files discrimination flap. One article on this list has received not a single visit since it posted. Thus rather than attempt to make sense of them, I’ll just list them in the order they appeared, with a bit of explanation for each:

- #36: Ligation Litigation, 160102: addressed a lawsuit against a Catholic hospital that would not permit the performance of a tubal ligation.

- #41: Ted Cruz and the Birther Issue, 160116: addressed whether the Canadian-born son of an American woman is a “natural born Citizen”.

- #42: Politicians and Statesmen, 160118: compared Republican voters to Democratic voters in terms of their concerns.

- #48: Inequities in the Justice System, 160128: gave an account of the arrest and trial of someone who happened to be walking near a minor crime and was charged based on very poor evidence.

- #49: Duchovny, Anderson, Sexism, and the Free Market, 160130: addresses the question of whether offering to pay the X-Files actor more than his co-starring actress reflects sexism in Hollywood.

- #52: The X-Files Sexism Debate, 160203: responded to comments on the first post on the subject.

- #54: Nudity as Free Speech, 160207: responds to one of my father’s last mailed clippings, about protestors using nudity to make a point.

- #58: Acceptable Killing In Our Society, 160222: responds to comments on Facebook about abortion, and whether our society finds killing acceptable.

- #60: Federalism and Elected Senators, 160229: discusses how United States Senators were chosen originally, how the seventeenth amendment changed that, and why some want to repeal it.

- #62: Gender Issues and Seating Arrangements, 160302: discusses the lawsuit against Israel’s El Al airline for moving a female passenger when a male passenger raised religious objections to sitting beside her.

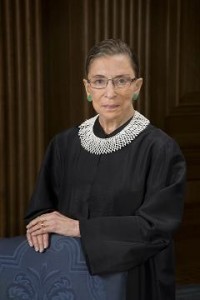

- #63: Equal Protection When Boy Meets Girl, 160303: concerns Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s view that abortion should be an Equal Protection right, not a Privacy right.

- #67: Dizzying Democrats, 160317: looks at the foolishness of the Democratic party primary process this year.

- #68: Ridiculous Republicans, 160318: gives the same kind of attention to the nonsense that has dominated the Republican primary process.

Bible/Theology

As mentioned, some of the political posts are simultaneously religious or theological, and I won’t repeat those here. There is one post that is really about everything, about the very existence of this blog, but which I have decided to list as primarily in this category: #51: In Memoriam on Groundhog Day, 160202. This is a eulogy of sorts for my father, Cornelius Bryant Young, Jr., who is certainly the reason for the existence of the political materials, as he significantly supported my law school education and then regaled me with questions about whether Barrack Obama was a legitimate President. He is missed.

I also wrote #65: Being Married, which is not exactly my advice but my choice of the best advice I’ve received over several decades of marriage. I’m hoping some found it helpful.

It should be noted that five days a week I post a study of scripture, and on a sixth day I post another essentially religious/theological/devotional post, on the Christian Gamers Guild’s Chaplain’s Teaching List. That is far too many links to include here, but if you’re interested you can find the group through this explanatory page.

Game-related

There were a couple game-related posts in the previous index, this time two of them specifically about Multiverser. There was some discussion about some of its mechanics on a Facebook thread, and so I gave some explanations for how and why two aspects of the system work–the first, in #38: Multiverser Magic, 160112: addressing difficulties people expressed concerning its magic system, the second, in #40: Multiverser Cover Value, 160114: explaining the perhaps not as complicated as it seems way it determines the effect of armor.

There was also another game-related post, #44: The Feeling of Victory, 160121: which discussed a pinball game experience to illustrate a concept of fun game play.

The award-winning Dungeons & Dragons™ section of the site (most notably chosen as an old-school gem by Knights of the Dinner Table) continues to get occasional notice; someone recently asked to use part of the character creation materials for work they were doing on a different game, and someone asked if I had a copy of my house rules somewhere, in relation to some specific reference I made to them. Although I’m running a game currently, I don’t know that anything new will appear there. The good people at Places to Go, People to Be are continuing to unearth the lost Game Ideas Unlimited articles and translating for their French edition. Unfortunately, Je parle un tres petit peux de francais; I can’t read my own work there.

Logic and Reasoning

Periodically a topic arises that is really only about thinking about things. That came up a couple times in the past couple months. first, someone wrote an article about the severe environmental impact of using the universal serial bus (USB) power port in your car to charge your smartphone while you drive, and in #45: The Math of Charging Your Phone, 160122, we examined the math and found it at least a bit alarmist. Then when people around here were frantically stripping local grocery store shelves of all the ingredients for French Toast (milk, bread, and eggs) because of a severe weather forecast, we published #46: Blizzard Panic, 160124.

On Writing

I left this category for last for a couple of reasons, several of those reasons stemming from the fact that most of this connects to the free electronic publication of my book Verse Three, Chapter One: The First Multiverser Novel, and I just published the last installment of that to the site. You can find it fully indexed, every chapter with a one-line reminder (not a summary, just a quip that will recall the events of a chapter to those who have read it but hopefully not spoil it for those who have not), here. There have been about seventy-five chapters since the last of these posts, and that (like the Bible study posts) is too much to copy here when it is available there. That index also includes links to these web log posts, but since this is here to provide links to the posts, I’ll include them here, and then continue with the part about the future of the site.

- #35: Quiet on the Novel Front, 160101: The eighth behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 43 through 48.

- #37: Character Diversity, 160108: The ninth behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 49 through Chapter 54.

- #39: Character Futures, 160113: The tenth behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 55 through 60.

- #43: Novel Worlds, 160119: The eleventh behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 61 through 66.

- #47: Character Routines, 160125: The twelfth behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 67 through 72.

- #50: Stories Progress, 160131: The thirteenth behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 73 through 78.

- #53: Character Battles, 160206: The fourteenth behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 79 through 84.

- #55: Stories Winding Down, 160212: The fifteenth behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 85 through 90.

- #57: Multiverse Variety, 160218: The sixteenth behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 91 through 96.

- #59: Verser Lives and Deaths, 160218: The seventeenth behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 97 through 102.

- #61: World Transitions, 160301: The eighteenth behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 103 through 108.

- #64: Versers Gather, 160307: The nineteenth behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 109 through 114.

- #66: Character Quest, 160313: The twentieth behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 115 through 120.

- #69: Novel Conclusion, 160319: The twenty-first and final behind-the-writings peek at Verse Three, Chapter One, Chapters 121 through 126.

The Future of the Site

I would like to be able to say that the future holds more of the same. There are still plenty of time travel movies to analyze; I have started work on the analysis of a film entitled Time Lapse, but it will take at least a few days I expect. This is a presidential election year and we have clowns to the left and jokers to the right, as the song said, and with the extreme and growing polarization of America there are plenty of hot issues, so there should be ample material for more political and legal columns. The first novel has run its course, but there are more books in the pipeline which could possibly appear here.

However, it unfortunately all comes down to money. My generous Patreon patrons are paying the hosting fees to keep this site alive, but I am a long way from meeting the costs of internet access and the other expenses of being here. Time travel movies cost money even when viewed on Netflix.

The second novel, Old Verses New, is finished–sort of. No artwork was ever done for it, and it is actually more difficult to promote articles on the Internet that do not have pictures (frustrating for someone who is a writer and musician but has no meaningful skill in the visual arts). More complicating, Valdron Inc invested some money into it, paying an outside editor to go through it, and they still hope to find a way to recoup their investment at least. I might have to buy their interest in it to be able to deliver it to you, and that again means more money.

So what can you do?

If you are not already a Patreon supporter, sign up. A monthly dollar from every reader of the site would not make me wealthy, and probably would not cover all the bills, but it would go a long way in that direction. Even a few more people giving five or ten dollars a month to keep me live would make a massive difference. I think Patreon also has a means of making a one-time gift, and that also helps.

Even if you can’t do that, you can promote the site. Whenever there is a new post or page here you think was worth a moment to read, take another moment to forward it–it is easy to do through most social media sites, some of which have buttons on the bottoms of the web log pages for quick posting, and in all cases I post new entries at Pinterest, Facebook, Twitter, Google Plus, LinkedIn, and even MySpace, all of which have some way of easily sharing or recommending posts. Let people know if there’s a good political piece, or time travel article, or whatever it is. Increased readership means, among other things, an increased potential donor base–support to keep us alive here.

There are other ways to help. Several time travel fans have over the years provided DVD copies of movies, either from their own libraries or purchased and sent directly to me, all of which have been analyzed. I now also have the ability (thanks to a gifted piece of not-quite-obsolete discarded technology) to watch YouTu.be and Netflix videos on my old (not widescreen) television, and with some difficulty to watch other internet videos on borrowed Chromecast equipment (not as satisfactory–can’t pause or rewind without leaving the room to access the desktop). Links to (safe and legal) copies of theatrically-released time travel movies make it possible to cover them now, for as long as the money keeps me online. (Yes, even “free” videos cost money to see.) One reader very kindly gave me a Fandango gift card to see Terminator Genisys in the theatre, which was a great help and enabled me to do the quick temporal survey published here, although I had to obtain a copy of the DVD to do the full analysis web page (it is nigh impossible to take notes in a darkened movie theatre, and very difficult to get all the vital details from an audio recording).

You can also ask questions. I don’t check e-mail very often (seriously, people started using it like an instant messaging system, I have cut back to every three to six weeks) but I do check it and will continue to do so as long as the hosting service and internet access can be maintained; I interact through Facebook and (to a much lesser degree) the other social media sites mentioned, and often take a question from elsewhere to address here. That gives me material in which you, the readers, are interested. I do write about things which interest me, but I do so in the hope that they also interest you, and if I know which ones do that helps more.

So here’s to the future, whatever it may bring, and to the hope that you will help it bring more to M. J. Young Net and the mark Joseph “young” web log.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Note that this form will contact the author by e-mail; to post comments to the article, see below.’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]