This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #140, on the subject of Societal Implications of Romans I.

We began this miniseries with The Sin in Romans I, where we stated

…ultimately there is only one sin listed in the first chapter of the Book of Romans:

…they did not give Him the glory or the gratitude that they owed Him, robbing Him of what He justly deserved….

We were deriving that from Romans 1:19ff. We then continued in Immorality in Romans I to explain that the “sins” we see described in that first chapter–the immorality, homosexuality, and total depravity–are not given to us as the proof of guilt but as the demonstration of punishment, that God punishes those who fail to recognize and thank Him by delivering them to the desires that destroy them. We ended that article with the thought

…if these are the punishment of God, why would I want them? Obviously, there is this draw that they have, because people are drawn into them, and many Christians will admit being tempted in those directions. The black hole of death pulls everyone toward it. The message of the gospel includes that Jesus saves us from this, that He enables us to be free from this death.

Then I noted that there was something else, something I had missed before.

That is where we are today, but to get there we are going to begin with a meandering discussion beginning with divorce law.

This has been not true for so long that some of my readers might be surprised to discover it was ever true. At one time, when a man and a woman signed their names to a piece of paper and swore before a public gathering that they would remain together for their entire lives, the government regarded those to be legally enforceable promises which it, the public at large, and the couple themselves fully expected they would keep. The part about “better or worse…rich or poor…sickness and health” underscored this: there were no outs. In England, if you wanted a divorce you often needed an Act of Parliament.

Of course, exceptions were made, what some will remember as “divorce for cause”. The promises that were made to each other included loving and caring for each other, and forsaking all others. If it could be demonstrated in court that one party had breached those promises, the other party was entitled to damages, including dissolution of the marriage. If the husband beat the wife, or abandoned her; or if the wife was sleeping with the neighbor–these were causes, breaches of the promises, and the injured party could be released from the obligation, often with compensatory damages in property settlements or alimony.

Usually.

By the middle of the twentieth century, affluent Americans who believed that they had earned what they had, and forgot that God had given it to them, began to be bored with monogamy. They felt like they should be able to divorce each other for no better reason than that they wanted to marry someone else, to find “happiness” with another lover. Hollywood gossip certainly fueled this–the stresses on the marriages of movie stars who were frequently separated working on different projects, frequently put into close relationships with other actors, and adored by fans who made them believe they deserved better caused many of them to fail, and the tabloid press popularized the idea that a star or starlet was escaping a bad relationship for a better one. Ordinary people thought that happiness was found in leaving the wrong person and finding the right one. The law in most places, though, was very much against them: you could not be divorced for a whim, only for a cause, a breach of the promise by one party against the other.

And the law was strict. There is a New York case in which a couple wanted a divorce but could not get one without cause, so the husband arranged for his wife to have an affair with his best friend, and they went to court and presented the matter to the judge–and the judge said no, that since the husband colluded in his wife’s infidelity he could not claim that he had been harmed by it, and therefore had no cause for a divorce. People were being forced to stay married to each other for no better reason than that at one time years before they promised each other and the government and the world at large that they would.

And somehow we no longer thought that a good enough reason. Why should you have to do something just because you promised, and benefited from the promise?

Gradually over several decades we changed those laws, to allow ourselves to break those promises. In the wake of that, the upcoming generation saw that the promises were becoming meaningless, and we entered the beginning of a “sexual revolution” in which such promiscuity became more open, accepted by larger and larger segments of society. Today promiscuity is the assumed norm. Unmarried adult virgins are treated as a comic element in popular media, a rarity, and sex among teens is expected even by their parents who don’t counsel them to wait but to be careful when they don’t.

And the law has moved to a place where it says, it is nobody’s business whether you have sex, whether you break promises made to a spouse, whether you get your pleasure from the opposite sex or the same sex. Follow your own moral compass, and if you don’t like where it points, break it and go where you want.

In the process we have lost the ability to commit, to keep promises, to love and trust each other. That is a serious loss.

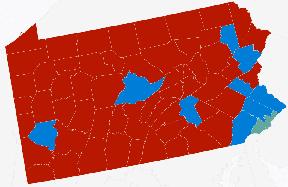

This was the part I did not see a decade ago when I taught that class (or three decades ago when I taught Romans to those college students). I could see that the immorality, the homosexuality, and the depravity were punishments on individuals who were destroying themselves because they refused to acknowledge God. What I did not then see was that it was bigger than that. It was not that Joe would not acknowledge God and now was having an affair with Alice, or that Bill was rejecting God and now found himself in a relationship with Steve, or that Mary ignored God’s kindness toward her and now could not figure out what was right and what was wrong. That was all true, but it was also true that there were others who had failed to acknowledge God who still lived moral upright lives, who were not suffering from the punishment Paul described. It was not targeting every individual evenly.

However, it was targeting society. People who kept their marriage vows started to discover that their spouses did not. People who embraced only heterosexual relationships discovered that they had homosexual children. People who lived moral lives based on a moral compass that followed sound principles but not God found that those around them, even those closest to them, could see no reason to follow those principles and were ready to do whatever profited them, whatever felt good, whatever they wanted. The society that rejected God, the society that failed to acknowledge Him, was falling into a downward spiral into depravity.

The wrath of God has come upon us. We can see it in the world around us, and as Paul said, it proves that God has begun the end of the world with the judgment of those who reject Him.

There is at least one more piece to this miniseries, because this is not the end of the story.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Note that this form will contact the author by e-mail; to post comments to the article, see below.’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]