This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #90, on the subject of Footnotes on Guidance.

Recently I have encountered someone several times who appears to me to be struggling to find God’s direction. I could be wrong, and in any case we have no relationship which forms a basis for me either asking or advising. Yet I was considering what advice I might give, and a number of thoughts came to mind.

There is a significant chapter on Guidance in my book What Does God Expect? which is in the main a reworking of the earlier web page Objective and Subjective Christian Guidance. This present work does not touch on that significantly, and I still regard that an important part of finding God’s direction in our lives. This is rather a more informal collection of observations about that direction as we experience it.

The individual in question was suggesting an interest in a particular direction; I asked why, and was given a reason which seemed from my experience to be inconsistent with reality–that is, it was thought that this direction would make money, and I have been down that path many times and never profited financially from it. Since I take it as essentially a ministry direction (although not everyone would) I was a bit repelled by the reason. Yet as I contemplated it I realized that there were aspects to this I had not considered. One is that I have often pursued what I perceived as a ministry direction with the notion somewhere in mind that it might incidentally make money; I just had not listed it first on the expectations in most instances (although sometimes it may have been second or third). The other was more complicated, but I think, too, more important.

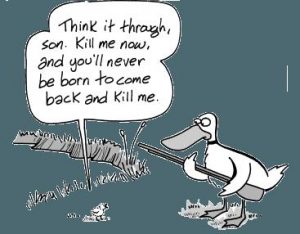

It seems to me that God sometimes directs my path by letting me see reasons for something which ultimately have little or nothing to do with why He sent me that direction. That’s not to say He lied to me; it’s more to say that I don’t get to know the plan, only my next task within it.

The example that springs to mind occurred when I was in college, having finished two years at Luther and started at Gordon. I had placed out of the first three terms of music theory and had not yet decided whether I should be a music major or a Biblical studies major. My career objectives were to become a Christian rock recording artist and performer, and I could see that either direction might be valuable. Yet at some point I came to the conclusion that a degree in Biblical studies would aid my career in Christian music more than a degree in music. I thought it might open doors, that people would be more interested in a Christian singer with a degree in Bible than a musician who happened to be Christian.

I am certainly not going to say that the degree in Biblical studies did not help my career as a musician. It has contributed significantly to the lyrics of my songs and “patter” in my stage presentation. However, that “career” has been at best spotty, and I do not think anyone ever asked me about my theological degrees (I got one from Luther also). Having a degree in Biblical studies did not do much for that career. It did, however, open the door for me to work at WNNN-FM, and gave me a solid foundation for the beginnings of my public teaching ministry there. That in turn, in a very odd way, began my notoriety as a Christian defender of role playing games, and the combination of my degrees and my role playing game connections brought me to the place of being Chaplain of the Christian Gamers Guild, writing several books, and writing for many web sites including this web log. God was indeed preparing me for ministry; He just was not preparing me for that ministry.

Getting back to that young believer who appeared to be seeking God’s direction, I wrote a note suggesting a possible path, and after a week or so received no reply. I had written previously, a month ago, on a similar subject, and that had not progressed far, so it is possible that my correspondent had decided not to pursue anything I suggested and also decided not to tell me this. I am not offended; there is no obligation to me. However, that caused me to think of another observation: God often leads us where we had no desire to go.

It was 1997. I was struggling to get Multiverser into print and promote it. As part of that promotional effort, I polished up an unpublished article I had written almost a decade before, entitled Confessions of a Dungeons & Dragons™ Addict, and found a space on the Internet to post it. It got a fair amount of attention, and I received an e-mail from a Reverend James Aubuchon, who together with two others had launched an organization named The Christian Role Playing Game Association. He was inviting me to join. I declined politely. I am not a joiner, I was on dial-up and needed to spend whatever time I had online to promote the game that was expected to make me if not rich at least solvent, and I wasn’t particularly interested in such a group. However, within a few weeks someone who was playing the game wrote to tell me that someone in that group was making negative statements about it, so I felt it necessary to join and address these (which were apparently entirely resolved before I got there). Once I was a member I began to become involved, I became interested, I got asked to do one thing and another and wound up temporarily stepping into the Chaplain’s office when it was vacated by the original Chaplain who felt that it was incumbent upon him to step into the Presidency when both the President and Vice President had resigned. Along the way the outgoing President changed the name to the Christian Gamers Guild. I don’t know what I did as Chaplain that first year, but apparently they liked me and when finally elections were held I was elected to continue as chaplain–and re-elected to the two-year position every even-numbered year since. It has opened doors for ministry in places I did not know existed, some of which in fact did not exist when I was in college. God has taken me on an unexpected path that caused me to think about issues no one else was addressing, write articles and books no one else was writing, and minister to people no one else was reaching. He did it by pushing me into a place I did not want to go.

So to any young believer seeking God’s direction, let me give this advice. God is going to lead you. He is not necessarily going to lead you where you think you are going, nor tell you the plan in advance, and sometimes He is going to open doors to possibilities you did not foresee and which you think are not where you want to go. If there is not a very good reason not to go there, take the open door, explore the possibility that does not sound like what you wanted or expected, because that’s often the way God is taking you to get you to places you never imagined going.

That, anyway, has been my experience, and while I have disappointments in my own hopes and expectations not having been realized, I ultimately must admit that what God has done with me has been very special, unique as far as I am aware, because I let Him take me where I did not intend to go and went for reasons that ultimately proved to have nothing to do with His plan.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Note that this form will contact the author by e-mail; to post comments to the article, see below.’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]