The Book

Beginning in July 2009, all Examiners were asked to contribute articles to the Info 101 project, an effort to provide answers to common questions in our fields. Thus a series of Temporal Theory 101 articles were written, covering in brief various terms and concepts used in connection with time travel in movies.

Not unexpectedly, the theory articles also brought questions and comments. Many of these were answered in the comments sections of the articles, but there was one respondent who raised several points requiring a clarifying article, this led to additional articles as answers to questions.

Confusion about time travel theory was still unresolved, with some readers challenging whether we could really know anything at all about what happens if you travel through time. Thus a second theory series, Temporal Theory 102, was created to address the issues in more detail and provide some of the answers hitherto oft-repeated in e-mail correspondence. That series has been consolidated to this article.

Periodically readers criticize this series based on the assertion that since no one has ever traveled through time (out of sequence) we cannot really know what would happen, and our assertions that this must have happened for the story to work or that this could not have happened as presented in the story are not defensible. There is certainly a level on which this is true. But it is not rational to say that anything is possible, nor to say that we know nothing simply because we cannot demonstrate it experimentally. For example, we have a pretty good idea what would happen if gravity were reversed, even though we have no means of reversing gravity. Thus it might be worthwhile to put a few articles into the question of explaining what we think we know and why we think we know it, and to look at the assumptions behind these conclusions.

If we are going to look at each of the three major theories, it makes sense to begin with fixed time theory, in part because it is highly popular among physicists (which in some minds makes it the true theory scientifically) and in part because quite a few time travel stories attempt to explore worlds in which fixed time is assumed. It also becomes the base against which other theories are contrasted, with parallel dimension theory also having a following among physicists but its distinguishable cousin divergent dimension theory being preferred in fiction, and various incarnations of replacement theory, some defensible and some not so much, being the most commonly presented understanding of time in most stories. Before we examine these individually, let's be clear on the distinctions between them, in simple terms.

Fixed time theory views all of history as already completed; time is not exactly an illusion, but the way we experience it is. It might best be understood by speaking of a road that runs from your house to the store, and your travel along it. The road exists; the store awaits ahead. Your movement does not cause the store to come into existence, but only brings you to it. In the same way, your death (for something that is ahead for at least most of my readers) stands at a specific moment in the future, and you are approaching it. It has in some sense "already" happened; you just have not yet reached the moment where it exists. You feel as if you are making choices that bring you forward in life, but in some sense you are only acting out what you are destined to do. Thus if you are going to travel to the past, your departure from the future has already occurred and so has your arrival in the past, and everything which from your perspective you are going to do you have from another perspective already done. Thus you cannot change the past, because the past is already written; you cannot change the future, either, because that, too, is already written.

This flies in the face of our belief in our own ability to change the world, that we make choices which become causes which have effects. There is a degree to which it seems irrational to claim that were we to travel to the past, we could not make choices that would change the past. This thus gives rise to multiple dimension theory, in its two major forms. The one more embraced by scientists asserts that parallel dimensions already exist, and that were you to attempt to travel to the past you would find yourself in the past of a seemingly identical universe, which you could change without incident because it is not really your past, but the past of a world you cannot distinguish from your own until you alter it. The one more embraced by writers suggests that when you arrive in the past, that instantly changes the past, but since the past cannot change it creates a separate universe, a divergent dimension which diverges from that point of arrival and continues with its own history into the future, without changing the events of your universe of origin, from which you vanished.

There are quite a few variations of replacement theory, but they share in common the idea that if you travel to the past you can change your own history. Whether there are other dimensions is irrelevant; there is only one history of the universe, but it is mutable. Whether the future already exists is also irrelevant; we can change it as easily as we can change the past.

With that groundwork, we will look a bit more closely at the assumptions and logic of each theory.

In considering the logic of time travel, the first issue to address is the nature of time itself. Two principle forms are logically plausible: either all of time exists in some static form from beginning to end (or eternity to eternity), or only the present moment exists, the past lost and destroyed, the future not yet created. Either view is defensible. However, from a time travel perspective, if only the present moment exists time travel is impossible nonsense: you cannot go to a place that does not exist. Thus we can have the Rip Van Winkle-type story exemplified by Buck Rogers in which the character sleeps or is in suspended animation and emerges in the future, and stories like Minority Report and Next in which the character is able to predict future events, but not one in which a character travels to the past. Time travel of that sort seems to require that something like a "timeline" exists, that the past is still the present "somewhen", and the future is "somewhen" to which we can travel.

Some avoid the "timeline" with a rather more complicated "timeplane", that is, movement along many parallel timelines which are staggered along the same events. By moving laterally across time, you travel to what appears to be the past or future, but what is actually a separate universe lagging or leading our own. Thus the future and past of our universe do not exist, but are duplicated in other universes also without futures or pasts. We cannot travel to our own past, but we can travel to something indistinguishable from it, and change it with impunity because it is not our universe. This will be considered further in discussing parallel dimension theory.

The very concept of a "time line" suggests that time is a dimension--not in the sense of another universe, but in the sense that length, width, and height are dimensions. Some insist that this is not true, that time is different in kind from these; yet despite the differences, time has the same impact on reality as spatial dimensions, other than that it is what we can call the dimension of change: absent time, everything would remain the same, because change implies time, a "before" and an "after". We can see that time is like a spatial dimension with a simple thought experiment.

The corner of the desk is a point in space; if you place a book there, it occupies that point in space, and you cannot place another book in the same place. Suppose that the book is actually an object with no dimensions, which occupies a point to the exclusion of all other objects. In space with zero dimensions, that is all that can exist. If, though, we take the edge of the desk to be the first dimension, we see that we can place other books along the edge, but only one at that point that we call the corner. However, if we then take the perpendicular edge as defining a second dimension, the surface of the desk becomes a two-dimensional space, and we can place a second book at the same point along the first edge by placing it at a different point along the second edge. It is thus in the same place in one dimension by being in a different place in the other. We can repeat this by adding a third dimension, stacking the second book on top of the first, at which point both books are in the same place, on the corner of the desk, in the two dimensions that define the desktop, by being in a different place in the third.

We could imagine a fourth spatial dimension, such that two books can be in the same place on the corner of the desk touching the desk by being in different places in this fourth spatial dimension; but we can also arrange for the two books to be in exactly the same place in those three dimensions by removing the first and replacing it with the second. We then have an object in the same place in three dimensions because it is in a different "place" in the fourth. Time is thus a dimension similar to the spatial ones, and arguably could exist very like a line or fourth axis on a graph.

In order for time travel to be possible, time must be a dimension very like this. The questions are whether we can move to other points along it (which is assumed by the concept of time travel), and whether it is mutable or fixed. That is the issue to be addressed next...time.

In discussing the nature of time we noted that unless a time traveler goes to other universes time must be something like a dimension, and thus that something we might call a timeline exists from the distant past through the present. We might ask whether the line continues into the future, but that is already part of the more basic question: is it fixed, or mutable?

Advocates of fixed time theory maintain that time is immutable, that the past cannot be changed. What escapes notice in this is that it also means that the future cannot be changed, either. It is easy enough to suppose that everything James Cole does in the past in 12 Monkeys he was destined to do in the past because he had already done it, but what is overlooked is that for the young James Cole watching in the airport, everything he is going to do in the future is equally destined. Thus when the fixed time theorist says that you cannot kill your own grandfather because we already know that you did not do so, implicit in that is that you have no control over your destiny, that all your future choices are already made, that you are fated to a life you have not yet chosen but cannot avoid choosing.

Most of us intuitively balk at this idea that we have no free will; it seems as if we do. That, though, is an inadequate basis for concluding that we do. It is certainly arguable that we will do what we, by heredity and environment, are programmed to do, and that this feels like freedom because all the constraints are internal, within our own personalities. It is similarly possible that the entire universe is so programmed, that just as billiard balls deflect at predictable angles everything in the universe will follow a predetermined sequence of events. The problem is that once time travel is introduced you have the possibility of an instability in the programming process. What is to prevent the program from looping with the command A=A+1, or A=-A, for causes in the future to have effects in the past that alter those causes in the future? Fixed time advocates assert that this cannot happen, but the basis for that assertion is circular, that if it did, it would change the past, and since you cannot change the past, whenever you travel to the past you begin a trip you have already completed.

Yet even given a deterministic model of human choice, it is difficult to imagine that no trip to the past would ever alter events in a way that would change the factors determining those choices. If on Monday you ate a hamburger and got sick, on Tuesday you might send a message to yourself that says "don't eat the hamburger", and if having received the message you chose not to eat the hamburger you did not get sick, then on Tuesday you would not send that message. Fixed time advocates assert that you could not do this--either you could not choose to send the message, or having received it you could not choose not to eat the hamburger. On the other hand, if having turned right on Broad Street you later discovered that there was a terrible accident to the left on Broad Street which you avoided, you could send yourself a message that said, "don't turn left on Broad Street," and your previous self could receive that message and obey it, because that does not change what he would have done anyway. At this point, it appears that the universe, or whatever it is that prevents certain willed acts but not others, has sufficient intelligence to foresee what acts in the future will alter the past and which will not. It suddenly seems to become a matter of divine intervention, of God under a pseudonym preventing catastrophe.

To the fixed time advocate, though, time is not at all like a sequence of choices, but like a puzzle that fits together only one way, and we discover how it fits as we live through it. The events in our lives are like tiles in a mosaic being constructed by someone else, but that there is no one doing the construction and no one planning the pattern, and yet somehow it all fits properly.

Fixed time thus poses some intellectual problems in regard to choices and future events which it tends to gloss. It creates a world in which I cannot help writing this article and you cannot help reading it, because we are destined to do what we do not know we have already done in the future. We have no control; it is an illusion. We cannot even control whether or not we believe in fixed time.

Faced with the unavoidable conclusion that if time is fixed choice is illusory, some in seeking a way of changing the past resort to the theory that anyone who seems to travel to the past actually travels to another dimension. There are variations on this, the most significant being between those who believe that those parallel dimensions have always existed alongside our own and those who believe that arriving in the past creates a different dimension with a different history which diverges from the original history at the point of arrival, but in all cases the point is that you can change history because it is not really your history, it only looks like it.

The theory is supported by certain observations in physics, mostly involving the appearance of photonic interference, that could be explained by the existence of a nearly identical universe alongside our own. It is not certain that there is such a parallel universe; other explanations of the phenomena are possible. Yet granted that such universe or universes exist, there are still two significant issues. The first is whether the existence of a nearly identical parallel universe means that anyone attempting to travel to the past would necessarily go there. There is a Newark in New Jersey and a Newark in Delaware, but a good Global Satellite Positioning System device will send you to the one you specify, and the fact that there is a Newark in Delaware doesn't mean that if I'm in New Jersey and I go to Newark I will necessarily travel to the other state. The existence of such a universe, if it were certain, does not prove that it would be the de facto destination of all time travelers.

The second issue is whether such dimension travel really is what anyone means by the words "time travel". If I want to go to Disneyworld and end up at Six Flags Great Adventure, I might not know the difference for some time; but they are not the same place. If I am attempting to reach my own past and land in something that looks like my past, perhaps meet someone who seems to be me, but is not part of the same history, I did not really travel to the past; it could as easily be a well-programmed animatronic theme park. These people who seem like my family are not and never will be my family. (For more on this, see The Two Brothers: Why Parallel Dimension Theory Is Not Time Travel.) Thus if the question is whether time travel works by taking the traveler to another dimension, then it seems to be saying that time travel, as we mean the phrase, does not actually work, but that anyone who believes he has traveled through time has been deluded by reaching another dimension that looks as if it is the same.

As already stated, parallel and divergent dimension theories are distinct, but share these common features. They also have distinct problems, and so we will address them next.

As we noted, parallel and divergent dimension theories have some common problems, but they also have some distinct problems. This time we will look specifically at the theory of parallel dimensions, that the other universe or universes already exist and we travel to them.

Implicit in the theory is the belief that such parallel universes are exactly like our own in every detail until a time traveler arrives and alters them. Thus each individual dimension has its own fixed time, with all the inherent determinism involved, but without the problems of free will causing paradox because we are not interfering with our own past. A grandfather paradox is not a problem because if you kill the person who would be your grandfather in this universe, it has no impact on your real grandfather who is alive in another universe. On the other hand, a predestination paradox is considerably more complicated, because if you marry the woman who would have been your grandmother, her descendants do not then include you, because the woman who actually is your grandmother is in another universe married to your grandfather, who is not you.

More complicated, though, is that it is assumed that when we travel to another universe it is identical to our own until we change it. This fails a simple logical consideration. To begin, either there is an infinite number of such universes or there is a finite number; either way, the odds are against us being the first to discover time travel, and the greater the number of universes the worse those odds become. Some hold that such universes are temporally linked, such that if you travel a hundred minutes into the past you cross to that universe a hundred minutes behind our own, with ninety-nine universes intervening at one-minute increments. (Minutes are used here for convenience; whether they are at steps or on a continuum is irrelevant, but steps are easier to grasp.) Let us then suppose that Traveler goes from our universe, H for home, one minute to the past to universe I, and he interferes with events in universe I such that his alternate self in I does not in turn travel to J. That means that the history of I is now different from the history of H, but since no traveler arrived in J, its history will be the same as H and its Traveler will travel to K, changing the history of K. This one time travel event thus alters the history in half of all existing universes, between those from which a time traveler departed and those to which a time traveler arrived. Yet if we are not the first universe in line, this has already happened to our universe and to all the universes adjacent to us. Therefore the parallel universes which would theoretically be identical until altered by a time traveler will already have been altered by many time travelers before we arrive (as probably ours will have as well, although we might be ignorant of that fact), and we will not have the predicted experience of being in a universe entirely like our own.

Of course, not every version of parallel dimension theory has them so linked temporally; but that part is irrelevant except to make the image simpler. If a dimension traveler arrives in some other dimension and prevents his own departure from it, it divides all histories into two versions; and if it does not do so, then we assume that a time traveler from some other dimension could arrive in ours and prevent our traveler from departing, but at the same time not do so because our traveler departs--exactly the kind of paradox this theory was supposed to resolve.

The only way to avoid this is to demand that the same things happen the same way in every universe; but in that case you have not solved the problems of fixed time, because even with an infinite number of such universes extending infinitely forward and back through time, once they are all linked such that the same history occurs in each, you merely have fixed time on a larger scale.

It is evident that parallel dimension theory does not resolve the paradox problems it was intended to resolve. Yet we also noted that there is a second distinct type of alternate universe theory, divergent dimension theory. According to this theory, when a time traveler arrives in the past, he creates a new history and therefore a new universe which branches from the original universe. In that sense he has landed in his own past; but he does not thereafter alter his own past, because by landing in it he has split this universe from that one, not changing anything that was his history but instead forming a different set of events that are not his past. This is the theory that was used in Back to the Future part II, in which Doc explained that they were in the wrong version of history, a branching line from an alteration made at some point in the past.

In some ways the biggest problem with this theory is in the laws of thermodynamics, specifically the conservation of matter and energy, that matter and energy are neither created nor destroyed. You can turn matter into energy and energy into matter; but where do you get all the matter and energy to create a new universe? Some assert that this is a function of the time travel device, but in practical terms it would require the conversion of all the matter and energy of the present universe in a perfect conversion to create the matter and energy of the new one. It thus then falls back on some version of Schrödinger's Cat, to say that matter and energy are not really configured in just one way but in many ways of which we perceive only one. Other dimensions don't really have their own matter, they have ours, arranged differently. It is noteworthy that Schrödinger created the illusration of the cat to show how absurd such an idea is, but those who embrace the idea embrace the illustration as not at all absurd.

Divergent dimensions avoid the problems mentioned with parallel dimensions, but still have problems. They share with parallel dimensions the simple fact that the traveler is not in his own past. To illustrate, if a man's younger brother dies and he devotes his life to developing a cure and taking it to the past, once he has cured his brother and returns to his own time, either he will be back in his original universe where his brother is still dead, or he will be in the universe in which he saved his brother, but his alternate self will be his brother's only brother, a man who never did any of those things because his brother never died. It is not really time travel, in that sense.

Divergent dimension theory solves another problem, but in doing so creates yet another. If Traveler reaches the past and prevents his parallel self from traveling to the past, there are then two of him in that universe (and none in the original after his point of departure). The past does not revert to what it was, and there are no other universes created that are altered. Further, if anyone else travels to the past, they also will arrive in a universe exactly like their own history, and create a new universe diverging from it. However, if the traveler does not prevent his other self from making that same trip, then when his other self arrives in the past, the first traveler will also be there--he must be, because his arrival is already part of the history of this universe from which the next one diverges.

Thus in the end, while these theories of dimension travel are interesting, they are nothing at all like time travel. We need a theory that both permits a traveler to arrive in his own past and leaves him free to do what he would do even if it is not what happened in the past he knows--a theory something like that represented in Back to the Future, Frequency, Deja Vu, Men in Black III, and other films in which time travelers change their own histories; but we need it to be logical and self-consistent.

What time travel enthusiasts want is a theory of time travel which allows the traveler to change his own past. Fixed time does not provide that, because the past is immutable, and indeed so is the future. Multiple dimension theories, whether pre-existing parallel universes or newly created divergent ones, do not provide that, because the traveler is changing someone else's history. We want a time travel theory that in essence allows us to replace the history we know with something else--hence, replacement theory.

Replacement theory has been analogized to rewinding a multi-track recording and recording over some tracks of it, such that everything is the same up to the moment the traveler reaches the past, but then new information is introduced in some places. It leads to several questions, and the possible answers create problems, but if certain answers are accepted we reach a coherent theory of time. What most objectors find difficult is that the theory holds that both the grandfather paradox and the predestination paradox can happen, but that there are consequences. In some versions of the theory it is possible to destroy time itself, that is, to bend time in such a way that it is, forever and everywhere, repeating a loop, perhaps as small as a day as in Groundhog Day or 12:01, or perhaps stretching across eons as in A Sound of Thunder or The Time Machine (whether the more recent version or the 1960 George Pal one). Thus some versions of the theory attempt to eliminate this problem with explanations of how history in essence corrects itself. There are also issues with randomness and free will that seriously complicate any version of replacement theory. Yet if we are going to have a theory of time in which a time traveler can alter his own history as we embrace in stories like Back to the Future, there must be a theory of time that allows the past to be changed, replaced by a different past; and we want it to be logically coherent and consistent both with our belief in free will and our scientific principle of causality. Thus over the next several articles we will examine various approaches to such a theory, and the advantages and problems of each.

The first thing to grasp is the management of the causal chain. Normally, A causes B, B causes C, and so on. What is clear is that if B is a necessary cause of C, and B does not happen, C does not happen--if there is no spark the fire does not start, if the kid does not run across the street the car does not swerve into the tree. That is not normally a problem, because events always happen in causal order, such that effects are always temporally subsequent to causes (the cause happens, then the effect). With time travel, though, suddenly C can become the cause of A--or conversely, C can become the cause of not-A, preventing A from occurring. Causes and effects are out of temporal order; yet they have to be present in causal order, that is, the cause must happen in the chain of events before the effect, even if the chain wraps from the future to the past. The problems occur when the cause-effect relationship is disrupted, either by making the cause of an effect the effect of its own effect, or by making the effect of a cause prevent its own cause. Most discussion of replacement theory debates the merits of various means of resolving these problems.

In attempting to address the complications of causal chains in replacement theory, some hold that it is possible to change only the little things in the past, and that the important things, the big things, will always correct themselves. You might kill Adolph Hitler before he comes to power, but you will not thereby prevent World War II or the Holocaust, because those are major events, and history will include them. You could kill your own grandfather, but someone else would marry your grandmother and produce a child similar enough to your father that when he in turn marries your mother, you will still be born. Similarly, if you marry your grandmother and become your own grandfather, you will pass to your father exactly those genes he needs to be the man who becomes your father. The future is thought to be self-correcting, such that you can change little things which do not matter, but the big things in the world would still happen on schedule.

The biggest problem with this solution lies in determining which things are little and which are big. If Johann Abrosius Bach had stopped at seven children, would someone else have written Bach's B Minor Mass, the many Bach Chorales, the Tocatta and Fugue in D Minor, and so much more, or would those pieces simply not exist? Given his impact on music (the chorales are a primary source for the rules of music theory, and the end of the Baroque Period in music is dated to coincide with his death), would western music be greatly different, or somehow the same despite his absence?

The Book of Ruth tells the story of a young widow from the insignificant nation of Moab who insisted on returning with her widowed Jewish mother-in-law to Israel, where she met and married a family cousin. Her great-grandson was King David, and she ultimately is an ancestor, both paternally and maternally, of Jesus of Nazareth, specifically mentioned as such in the Gospel of Matthew. Of course, Boaz could have married a nice Jewish girl instead; Ruth could have stayed in Moab. No one could have known that she would have a significant place in history when she married a young foreigner and became attached to his family.

The problem with saying that we can change the little things but not the big things is that we often do not know what the big things are. For something to prevent us from altering the big things while allowing us to change those things which will not matter is that whatever it is that does this must be omniscient and omnipotent--theological words used to describe God. I am a theologian who believes in God; yet I would not dare to presume that God will prevent any particular disaster, or to rely on Him as part of any theory of how things work. I believe in divine intervention, but in the main if God allows or forbids anything, He does so through quite natural means.

Which comes to saying that if indeed it is possible to change unimportant things but not important ones, then there must be a perfectly natural reason for this--and if there is, no one has yet suggested it. Either the past can be changed or it cannot; there is no way for the past itself to know what changes matter, or even what events are different from what "originally" happened in a history that has not yet occurred.

In trying to resolve the issues created by replacement theory, some assert that once the past has been changed it remains in its new form unless someone else from the future changes it to something else. This is a popular interpretation of Niven's Law, which asserts that in any universe in which history can be changed time travel will never be discovered, and is taken to mean that once the people in the future can fix whatever is wrong in the past, they will eliminate their need to create time travel because they have created the perfect past.

There are several problems with this, including that it ignores the desire to create time travel solely for the sake of knowledge. The one that matters most, though, is the issue of the causal chain. If Traveler goes back from 2020 to 2000 to change something and succeeds and returns to 2020, then his duplicate has no reason to make that trip and will not leave 2020 for 2000. This theory here says that this is not a problem because once the Traveler arrives in the past, he is part of the past, and he does not need to leave the future "again" to be in the past, as he is already there. Yet what if Traveler does leave from 2020 to travel to 2000, perhaps to change history from what it is (which he created) to what he does not know it originally was? Are there two versions of Traveler in the past, or only one? If there is only one, which future is he attempting to create? Thus this approach suffers from a problem similar to that of divergent dimension theory, only more so: if the duplicate traveler does not depart from the future, he is still present in the past, but if he does depart from the future it makes no sense either that he does or that he does not meet himself in the past.

The only logical way for the causal chain to play requires that if the traveler made a trip to the past, the traveler's duplicate must make the same trip to the past for the same reason with the same knowledge and abilities. If he does not do so, he erases his presence in the past. This then undoes the changes he made and restores the original history, which is how we get an infinity loop.

It has previously been noted that this interpretation of Niven's Law is not necessarily what Niven meant. He may have meant merely that free will is incompatible with the Novikov self-consistency principle, and therefore time travel will be impossible in any universe in which people have free will to change history. It is again wishful thinking; there is no evidence that dangerous things are impossible. However, this raises the issues of free will and randomness.

Time travel and parallel dimension stories sometimes speak of sideways time. The term is used to describe different concepts under different theories of time.

It is most commonly heard in connection with parallel dimension theory, in which there are presumed to be a vast and possibly infinite number of parallel worlds alongside our own. In some versions of the theory, these universes are all different, frequently very different, as their histories have diverged based on random variations in events over time; thus stories built on this concept are less about time travel and more about universes that are similar but distinct. The 1970 Dr. Who episode Inferno with Jon Pertwee is such a story, as is the original Star Trek series episode Mirror, Mirror and its Deep Space Nine sequel Crossover, and all the episodes of the series Sliders. In these contexts, sideways time means moving to a universe which has always existed as a distinct universe, that is similar to but divergent from a "home" universe.

In a purer version of parallel dimension theory, sideways time still indicates traveling to another universe, but that the other universe is identical to the "home" world. In some versions of the theory, these universes are offset incrementally, such that moving sideways across them gives the appearance of moving forward and backward in time, but that anything the time traveler does in one universe will change it without affecting any other. The problems with this concept are myriad, most notably that a single time travel event will disrupt the parallelism of an infinite number of universes, making all future sideways time travel unlike time travel because the parallel universes have all been put out of synchronization with each other.

The concept of sideways time is sometimes mentioned in connection with divergent dimension theory as a means of getting from the present universe to the lost original universe, although in most cases, such as in Back to the Future Part II, it is discounted as an impossibility. The original universe still exists in divergent dimension theory, but its integrity (the prevention of paradox within it) demands that it be unreachable from any diverging universe. Were it possible for someone in a divergent universe to return to his universe of origin at any point prior to his departure from that universe, he would have to create yet another divergent universe or all the advantages of the theory would be lost (paradox would not be prevented).

Illustrations of anomalies in replacement theory sometimes are perceived as suggesting the possibility of sideways travel to a previous version of history; however, under replacement theory the previous version of history is being erased as the new version is created, and thus there is never a corresponding "now" between the two histories. Under fixed time theory the concept is irrelevant: there may be parallel dimensions, but traveling to them is unlike time travel in any way and should not be confused with time travel.

The theory of two-dimensional time treats sideways time differently. In this case, time exists in complete form from beginning to end (or from infinite past to infinite future), but this complete history of the world can be changed by movement akin to sideways time, typically by the movement of time travelers to points in their pasts. The theory is that the arrival of a time traveler in his own past changes all of history from that moment forward, and so the universe shifts to a new timeline. In such circumstances, the old timeline becomes inaccessible, but objects and persons already severed from their own origins by time travel may continue to exist in the new timeline. Also of interest in this is the concept of supertime, a construction that attempts to use something like sideways time to allow change to propagate through the history of a new universe at a delayed rate. Again under this theory the original universe might continue but is inaccessible; sideways time travel is in one direction only.

In Looper, some actions done to the younger time traveler affected the older one instantly; similarly, in Back to the Future (Part I) there is evidence that Marty's future is changing and affecting him directly. On the other hand, in A Sound of Thunder the changes come in waves like ripples on a pond, and in Meet the Robinsons young Lewis is racing to beat the changes happening around him (although incongruously Doris vanishes instantly). The question is, given that changing the past changes the future, how quickly do those changes occur?

One possible answer is that the changes occur instantly, that if Marty prevents his own existence he instantly ceases ever to have existed. The most obvious problem with this is a sort of flicker history, the equivalent of an infinity loop oscillating between his existence and his non-existence, since of course if he causes his own non-existence he does not exist to cause it (barring Niven's Law) and so restores his existence only to undo it. How that would be experienced becomes the difficult question. The second serious problem is, as the movie illustrates, changing your history does not necessarily mean undoing your existence; events must play through to determine how the change impacts you.

A second answer is that such changes move at the speed of time. Sergiy Koshkin has suggested that the changes will never reach the time traveler himself, because they propagate at the rate of time, creating an alternate history and erasing the previous one, but allowing the future to continue based on the now-non-existent version of events. Thus even if the time traveler undoes his own existence he will not be there to undo it and history will revert to its original form, both the original and the altered versions of time exist at different points along the timeline. The changes never reach the time traveler who made them, because he is still racing ahead of them, keeping the same lead on the changes as he created by his trip to the past. This, though, creates inconsistencies in the causal chain at least from the perspective of time travel: a time traveler who prevents World War II who then fails to prevent World War II will find that when he travels back through time he passes through some periods in which the war happened and others in which it did not.

A third solution attempts to compromise, such that the changes propagate forward through time at faster than the speed of time, but the time traveler is able to outrun them, to reach his own future before the changes do, and have the world change around him when they reach him. This has story appeal: it allows our time traveler the opportunity to fix what he did in the past, but limits the time in which he can do this. However, it is difficult to find a logical basis on which to base a rate of change that is neither at the speed of time nor instantaneous, so this devolves to fanciful conjecture.

The best solution recalls the issue of the nature of time, treating time as having a static existence experienced as if in motion. This results in a solution in which change occurs instantly but is experienced at the rate of time. If we consider all of history as a complex set of related equations, A+B=C, C+D=E, E+F=G, the value of G is dependent on the value of A and changes the instant A changes; but the steps of the equations occur in sequence. In this illustration, we experience the steps at the rate of time, even though the changes stretched out in the future occur instantly--using a time machine to move to the future, we would discover the altered history already awaiting us. Thus in one sense if Marty undoes his own existence, he immediately ceases ever to have existed, while in another sense having undone his own existence he continues within history until the change plays through to the new altered history. As in the film, he has time to correct the problem, partly because it is uncertain whether he has ended his own existence, but also because his birth, still in the future, and his departure for the past, still in the future, are events that have in a sense "not not happened yet".

This thus gives us a logical basis for discussing how time travel impacts history, in that the changes are immediate but not experienced until we reach the points in time when they occur. It also becomes a logical basis for handling changes to history.

Once we have decided that it is possible for a time traveler to alter the past of the world from which he came, and that such changes are neither self-sustaining nor self-correcting, we have to determine what happens when history is changed. In this, the causal chain must be preserved--that is, no effect occurs if it is not preceded by its own cause. Pots of water do not boil if heat is not applied, the baseball does not fly out of the park if the bat fails to hit it, and events which are (always) the result (effects) of other events (causes) do not happen if the events which cause them do not happen. Thus Bob's arrival in the past is the effect of his departure from the future, and if he does not depart from the future he does not arrive in the past.

However, before he can depart from the future, there must be a future from which he can depart, a chain of causes and effects which create the world at the moment of his departure; and since the future cannot have occurred until those events create it, Bob cannot have departed from the future until there is such a history of the world, a history in which he did not arrive in the past. This we call an original history, original in the sense that it is what happened when Bob did not arrive within it.

It should be noted that the use of the word "original" here is with reference to this trip alone. Readers sometimes observe that it might be possible that other time travelers had already interfered with history. What matters is that the first time this time traveler makes this trip, he does so from a history in which he has not altered history by arriving in the past.

Fixed time theorists object that his arrival in the past is always part of history, because he will depart from the future. Notice, though, that the one who departs from the future has knowledge of the events which occurred in his past, now the future, because he experienced them as if in time. Thus the causal chain must have reached that point sequentially prior to his arrival in the past. To illustrate, Traveler awakens Monday morning, has a hamburger for lunch, dines with his girlfriend, goes home to bed, awakens Tuesday morning and sees on the news that his girlfriend was murdered Monday night. He leaps into his time machine and travels back to Monday afternoon, hoping to prevent whatever events led to her death, having such knowledge as was in the news concerning her murder. He cannot arrive on Monday afternoon until he departs from Tuesday morning; he cannot depart from Tuesday morning until he has lived through Monday. Whether or not he can otherwise alter events on Monday night, tracing the causal chain backwards demands that he has experienced the events of a history in which he did not interfere. The fixed time alternative not only means he cannot change history, it means that the future is already determined as well, and he is not really making any decisions but merely playing a pre-written script.

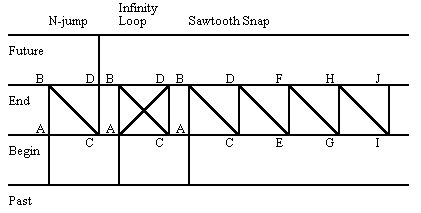

Thus if it is possible to change history by means of time travel, there must be an original history which is unchanged, and the arrival of the time traveler, in and of itself, alters that history. The issue of temporal anomalies arises, because as it happens there are exactly three ways in which a time traveler can alter events: he can create a new history that is self-sustaining, that is, which his younger self will create in the same way (an N-jump); he can restore the previous (or a previous) version of events and so create a cycling causal chain between two (or more) iterations of history each of which causes the other (an infinity loop); or he can create a new version of events that is different from all previous versions and will not repeat any of them (a sawtooth snap). These will each be considered in more detail.

There are three possible outcomes to changing the past; they are difficult to discuss in isolation from each other, but we will begin with the most desireable and possibly least likely, the N-jump, in which the traveler manages to create a self-supporting alternate history.

In its simplest form, the traveler is an observer, present in the past but not interacting with events. His presence might be observed, but has no impact on history. Since nothing has changed, history will unfold the same way, to the moment that the same person will make the same trip for the same reason, causing the same minimal changes in the past.

Similarly, the traveler might travel with a specific objective--perhaps to kill Stalin or prevent the assassination of Lincoln or Kennedy--and fail so completely that his effort is unknown to his future self. Although history has been altered slightly, it has not changed our time traveler, who will at the same moment be the same person making the same trip for the same reason, with the same outcome. History is stable.

From the perspective of the future, the N-jump is indistinguishable from fixed time, because when time is stable, all causes and effects exist in the only history anyone remembers. This applies even to the predestination paradox, in which the traveler causes events related to his own trip. Simple examples are Somewhere in Time, in which Elise seeks and ultimately finds Richard because he came back in time to find her, and Star Trek (2009), in which Spock gives Scotty the formula for transwarp teleportation that the latter has not yet invented. But to see how it works, Back to the Future provides a good example, because we see it happen.

In the stable history, George and Lorraine were brought together by Calvin, who used the name Marty; they named their third child Marty after him. That child traveled to the past, and was the Marty who brought them together. From the final history, it would appear that they met and married because their own child brought them together. However, we know the original history, that Lorraine's father hit George, Lorraine nursed him back to health, they kissed at the dance, and then married. We also know how Marty interfered with that meeting and then worked to fix it, creating the paradox.

Such outcomes are improbable, but not impossible. Ultimately the hope is that the next iteration of the time traveler will repeat his own actions and so create his own history.

Although the most desireable outcome of a time travel event is an N-jump, it is not the most probable. It is more likely that the past will be changed in a critical way that restores the original history, and thereafter oscillates between two iterations. The classic grandfather paradox is the obvious example: what happens if you kill your own grandfather before he has children? The obvious answer is that you are never born; if you are not born that breaks the causal chain, because you cannot travel to the past and kill your grandfather, and thus you are born, and you do, and history is trapped repeating two alternate versions forever: an infinity loop.

Killing your progenitor seems extreme, but infinity loops are a common probable outcome: any time a traveler successfully intentionally changes the past, he likely undoes his reason for doing so and restores the original history and his reason. Kill Hitler and he will never rise to power; however, without his atrocities no one will know about him, and you will have no reason to kill him, and so he will live and become the man you choose to kill.

It is possible, within very narrow parameters, to change the past and preserve the change. It requires preventing the time traveler from knowing that the change has been made, and thus only works for short trips with isolated time travel teams. The television series 7 Days has some potential as a model, although it requires some modifications. In general, an effort to change the past either succeeds and creates an infinity loop, or fails with the possibility of a stable N-jump.

Sometimes the acts of a time traveler will not result in the stability of an N-jump, nor in the repetition of an infinity loop, but in a string of unique histories. This can sometimes continue indefinitely, no two histories quite the same. The simple example is when the traveler meets himself. For clarity, we will use successive letters to identify successive iterations of Traveler.

Traveler A never met himself before he made his trip, but whether by intent or accident he met Traveler B. When B in turn makes his trip, he meets C, and thus C has the experience of meeting himself as B did--but not the same self. When B meets C, he remembers meeting A, but even if he tried to do so he cannot reproduce that encounter for C, because he is a different person than A. Thus C has a different experience, and is different again when he meets D, who is different when he meets E. Each history thus is different in the experience of Traveler's encounter with himself.

This sawtooth snap might stabilize into an N-jump if the encounter becomes self-supporting because Traveler is no longer different. It could instead loop back on itself, if the traveler avoids the encounter or repeats the actions of an earlier iteration.

This also occurs if an object is carried back in time only to return to the time traveler that much older to be carried back again. The watch in Somewhere in Time is an example of this: each time Richard takes it to the past it is a century older, and eventually it decays to worthless and the seqeunce resumes presumably with a new watch. The mediallion in Time Rider is similarly ill-fated, as the traveler loses it to the grandmother from whom he inherited it. TimeRider also includes Lyle becoming his own grandfather, setting up a similar sequence in which his own genetic identity constantly changes (barring self-correction or Niven's Law). A perpetually changing history is difficult to imagine but actually rather likely given the butterfly effect, which could result in an unending series of not-quite-identical histories.

The question is frequently raised: when a history ends, whether an original history of an N-jump or any history of an infinity loop or sawtooth snap, what happens to the people living at that moment? Do they die? Is it painful? Do they plunge headlong into some dark abyss of nothingness? The answer is difficult for some to grasp: they cease ever to have come into being.

At 8 A.M. Abe is having his usual workday breakfast of coffee and a toaster pastry. Bob is just getting out of bed, and Cal is finishing work on his new time machine. At nine, Abe punches in, Bob leaves for work, and an exhausted Cal goes to bed. Abe and Bob both have lunch around noon, while Cal sleeps. Abe goes home at 5, Bob half an hour later, and they each get dinner. Cal awakens at 7 P.M., and at eight he tests his time machine by traveling back to nine in the morning.

Abe is already at work. We can call him Abe 2, but he ate the same breakfast as Abe 1, will have the same noon lunch, leave work at five, get dinner, and by seven will be in every possible way identical to Abe 1. Technically, Abe 1 never existed, but he hasn't ceased to exist because he exists as Abe 2.

As Bob is leaving the house, his phone rings, and Cal persuades him to call out of work and meet him for brunch. There, while Cal 2 is sleeping, Cal 1 tells Bob 2 about the time machine. Bob 1 never comes into existence; that morning his life was diverted such that he became Bob 2 instead.

Then, at 8:00, unaware that Cal 1 has already done this, Cal 2 tests the time machine, traveling to nine in the morning, calling Bob, and in all ways replacing Cal 1. He alone remembers the day occurring twice, but it was the identical day. Bob never knew the day he went to work, and no one saw him there. Abe lived the day only once. Time continues with that as the only version of the day that was; the other has been erased and replaced.

What happens to everyone when the end of a history is reached is they return to who they were at the beginning of that history and live through the next iteration, all memory, all results of the time that passed undone. People who died have not yet died, those born or conceived not yet alive. They did not cease to exist when their timeline ended; they returned to its beginning to live through the new version as the first time.

In Kate and Leopold, Kate leaves her late twentieth century advertizing executive job to marry Duke Leopold in the late nineteenth century; Stuart is their descendant, proving they had children. Yet before Kate can marry Leopold she must be born, and thus there is a history in which Leopold does not marry Kate. Yet we know that he will marry someone; in fact, we know that he would otherwise marry Miss Tree, of the Schenectady Trees (the "Miss Tree" girl). In that history, Stuart will never be born, and it is likely that there will be other descendants instead. When Kate marries Leopold, those other people, the descendants of Leopold by Miss Tree, are never born. Yet the now eligible desirable high-society Miss Tree will certainly marry someone else, and that fortunate fellow will not wed whom he would have--whom he did when she married the Duke. The displaced bride in turn finds another groom, and in a ripple that passes through New York State's upper class scores of matches are shuffled, resulting a century later in perhaps thousands of people never born, thousands born instead.

This is the genetic problem: anyone from the future marrying someone in the past creates and probably uncreates innumerable lives. It is not absolutely necessary that the time traveler enters a relationship. Apart from Marty's specific efforts in Back to the Future, Lorraine would have missed connecting with George McFly and ultimately would have married someone else, possibly Bif. However, Marty created quite a stir; how many other girls may have ignored boys who simply were not him? The reverse effect also occurs: when in Millennium Louise brings Smith home from the past, are there women whose hopes of marrying him are dashed, who settle for another suitor sooner instead of snubbing a few more men in the hope that Smith's eye will fall on them? Is it possible that some years later Smith might have married someone else had he not been removed from history? In the flow of history, who is born is one of the most important factors in forming the future, and thus these relationships and the shifts they trigger are quite significant. The addition or subtraction of a single individual in any generation can ripple through the population in a very short time.

This is also why deaths matter. In the original Star Trek episode Tomorrow is Yesterday, Spock at first concludes that because there is no mention of Captain John Christopher in the historic databanks it is not necessary to return the accidental passenger to Earth, but then discovers that Christopher's as yet unborn son, Colonel Shaun Geoffrey Christopher, would lead the first Earth-Saturn mission. This is a dramatic example, but the fact that Captain Christopher might have had additional children is itself sufficient to make him vital to the preservation of history, and even the fact that any given individual might be perceived as a desirable mate by someone has the potential to change the future population of the world. Captain Christopher could have been Kirk's great-great-great-great-greater-than-that-grandfather--or indeed Spock's or McCoy's, and given the number of people aboard the Enterprise the odds are good that at least one of them would be impacted by the life or disappearance of this one person two hundred years in the past. You cannot make changes to the population with impunity; the consequences are too complicated to predict. Every individual matters, because each individual might influence who is born in the next generation, and one change in that will likely have more impact on the world as we know it than stepping on a butterfly in the Jurassic age.

Examples abound, notably in Timeline, in The Time Machine (the 1960 version), Men in Black III, and many others. It is a common problem and difficult to avoid--even in stories in which it is not evident, there is often the potential that the presence of the time traveler would disrupt a relationship, a butterfly effect type problem that cannot be prevented. It may be the most dangerous aspect of time travel.

There are undoubtedly more questions about temporal theory, and the author will gladly respond to comments and e-mail. From what we have covered, though, the reader should be able to analyze most time travel stories.

Analysis begins by determining where in the story we are. Some, such as Flight of the Navigator and Back to the Future (part I), begin with the original history and then alter it. Others, such as Terminator and 12 Monkeys, give us a final history or one much changed by the time travelers already in the past. The actions of the time traveler often need to be considered so as to extrapolate backwards to what happened in the original history. If the story contains a predestination paradox, a plausible original cause must be adduced that sets events in motion.

Once a plausible original history is reconstructed, the actions and the motivations of the traveler must be examined, with particular attention to whether he has somehow changed his own life, knowledge, circumstances, character, or motivation. If he is not what in the vernacular we call "the same person", he will not make the same trip. An N-jump--the desired outcome--requires that everything be exactly the same.

If the stable N-jump is not achieved, the question is whether the original history is restored creating an infinity loop, or a new version of events is introduced for a sawtooth snap. In the latter case the new history should be extrapolated to see whether it is likely to stabilize, loop, or introduce yet another history.

Details are extremely important. Predestination paradoxes involving objects looping to the past are fatal to time, but those involving information are not necessarily so as long as it does not undo itself. Marriages and deaths are very dangerous because of the genetic problem. On the other hand, even though the butterfly effect can have serious consequences, in analyzing a movie it is better to give it the benefit of the best possible outcome from the facts. Unforeseen changes can destroy any time travel event in actuality, but if the story says that the result was favorable and it might have been favorable, the improbability of that favorable outcome should be noted but not held against the possibility of it reaching that point. Put another way, if the story says that this is the condition of the world and it resulted from this time travel event, what matters is whether it might have, not whether it must have.

With that arsenal, the average time travel fan should be able to identify what works and what does not in a time travel story.