This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #360, on the subject of Voting in 2020 in New Jersey.

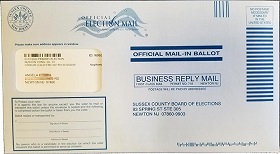

I was watching for my annual sample ballot, and realized that what I received instead was a mail-in ballot, and that due to its not entirely unjustified COVID paranoia the state wants all of us to mail in our votes. They are not opening as many polling places this year, and would rather no one come to them. (Given the public fights that have occurred over the current Presidental race, one might think that the disease issue is an excuse, but we’ll take their word for it that that’s the reason.) In the past such mass mail-in voting systems have been fraught with fraud, and already there are reports of fraud in the present election, but the penalties are fairly severe including loss of the right to vote, so the best advice is don’t tamper with any ballot that is not your own.

My initial reaction was to write this article on how to vote. Then I saw that both Google and Facebook were promoting pages on how to vote, and thought I would be redundant. Then I rummaged through the pack of papers which came in the envelope and decided that it was a bit confusing, and perhaps I should tackle it.

It is important to understand that your packet contains two envelopes, and you might need them both. Mine also contained two ballots, one for the general election and a second for the school election, so be aware of that as well.

You will need a pen with black or blue ink. Ballot readers cannot process red ink or most other colors, and pencil is considered subject to tampering.

The school ballot, assuming you receive one, is specific to your district, and probably is just candidates for the local school board. It should be marked and placed with the other ballot in the envelopes, as discussed below.

The general election ballot is two sided, at least in my district, with candidates for office and three somewhat extensive and controversial public questions on the other. Avoid making any marks outside those indicating your selections. The ballot this year includes:

- President Trump and his Vice President Pence, with those running against them;

- Senator Booker, with those running against him;

- one seat in the United States House of Representatives, specific to your congressional district

- Some number of county/local offices.

Each candidate name is in its own box, rows across identifying the office, columns down generally the political party.

In the upper right corner of each candidate’s box is a small hard-to-see red circle. fill in the circle completely of each candidate for whom you are voting. You are not obligated to vote for anyone simply to have voted for someone for that office, that is, you can decide to leave a row blank. There is a write-in space to the far right end.

In most districts, you will have to flip the ballot over to get to the ballot questions, and these are somewhat important this year. The questions are, of course, yes/no votes, with the little red circles at the bottom of the page below the Spanish text.

Question #1: Legalization of Marijuana.

The state wants to amend the (state) constitution to allow regulated sales of something called cannabis to those at least 21 years old. There is already a Cannabis Regulatory Commission in the state to control our medical marijuana supply, and they would oversee this. The bill includes a clause permitting local governments to tax retail sales.

It should be observed that the restriction to those at least 21 years old is likely to be about as effective as the similar restriction on alcohol use. On the other hand, a lot of our court and jail system is clogged with marijuana user cases. Yet again, whatever the state decides, marijuana use will still be a federal crime, and it will still be legal for employers to terminate an employee who fails a reasonably required drug test.

This would be a constitutional amendment, so if the change is made, it is permanent.

I have previously suggested issuing drinking licenses which I indicated could be used if the state decided to legalize other drugs.

Question #2: Tax Relief for Veterans

When you enlist in the military, it’s something of a crap shoot: even if you know we are at war when you enlist, you don’t know whether you will wind up fighting. Still, there is a benefits distinction between those who served during times of war and those who served, ready to fight if necessary, during times of peace. One of those distinctions is that those who were enlisted during times of war get property tax deductions, and those who are disabled get better ones. Question #2 would extend those benefits to veterans who served in peacetime, including those who are disabled.

Veterans get a lot of benefits; on the other hand, we should not begrudge them these. There might be a difference between those who fought and those who didn’t, but that’s not the distinction the law makes–it rather distinguishes those who served during a war even if they were behind a desk in Washington from those who served during peacetime even if they were part of military aid to other war-torn countries. There are good reasons to remove the distinction, and I’m not persuaded that the reduction in property tax income is a sufficient counter argument.

Question #3: Redistricting Rules

The United States Constitution requires a census every decade. The states are then required by their own constitutions to use that information to create new voting districts that more fairly represent their populations. This year the fear is that due to COVID-19 the census data is going to be delayed and will not be delivered to the state in time to create the new districts for the fall 2021 election cycle.

To address this, the legislature has proposed an amendment that states that if census data is not delivered to the governor by a specific date in the year ending 01, previous districts will be used for those elections and the redistricting commission will have an extra year to get the issue addressed.

It sounds simple and logical, but there are those opposing it as potentially racist and benefiting politicians, not people. On the other hand, it solves a potential problem before it becomes serious. It would apply to any future situations in which a similar information problem occurred, and while this has never happened before and might not happen even now, contingencies are worth having.

Submitting the Ballot

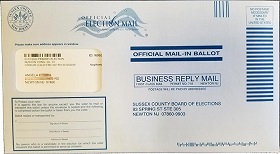

One of the two envelopes has some bright red and yellow coloring on it plus your name and registered address and a bar code. Once the ballots are completed, they go into this envelope. I will call this the ballot envelope.

It is necessary that the information on the flap of the ballot envelope be completed. This includes your printed name and address at the top and your signature, the same signature that is on the voter registration rolls.

Once you have completed this, you have three options, one of which creates more complications in filling out the envelopes.

One is to use the other envelope to deliver the ballot by United States Mail. This envelope has the postage pre-paid business reply certification, addressed to your County Board of Elections. I will call this the mailing envelope. If you do this, it must be postmarked not later than 8:00 PM Eastern Time on Election Day (November 3 this year) and must be received within a period of days specified by law. After having sealed the ballot envelope, place it in the mailing envelope such that your name and address on the ballot envelope appears in the clear window on the back of the mailing envelope, and seal that as well. Your name and address should be written to the top left on the front. It can then be mailed by any normal means.

The second is that there are reportedly ballot drop boxes, generally at polling locations, and you can insert the ballot envelope in the ballot box (without the outer mailing envelope) to deliver it directly to the board of elections. This too must be done by or before 8:00 PM Eastern Time on Election Day.

The third is that you can use either of these methods but have someone else deliver your ballot either to the ballot box or the mailbox on your behalf. No one is permitted to deliver more than three ballots, including his own, in an election, and no one who is a candidate can deliver a ballot that is not his own. A person who handles your ballot must put his name, address, and signature on the ballot envelope and, if mailed, on the mailing envelope.

So that’s the whole ball of wax, as they say. Remember, you should vote if you have reason to do so, but you should not feel obligated to vote for any office or any issue about which you are uninformed.