This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #0005, on the subject of An Image A.S.C.A.P..

At one time, if you wanted to hear music, you had very few options. You could learn to make your own, have family or friends perform for you, attend a concert (either buying a ticket or attending one paid for by a government or arts patron), or hire musicians to provide it. Technology changed that drastically, beginning with Thomas Alva Edison’s discovery that audio waves could be transformed into physical etchings and recreated as audio waves–the beginning of recorded music, the analog record. At that point you could buy a Victrola and purchase originally cylinders and later disks on which musicians had recorded their performances, and you could listen to them whenever you wished. (There were previously of course music boxes which provided a much narrower choice of songs and lower quality of tone, and player pianos and orchestrions, which were far more expensive and demanding to operate. Recorded music was a game changer, and these others are now novelties.) Musicians who once made money only by live performances now could make money by selling their performances to record manufacturers so that they could be heard by people who never saw them.

The game changed again with the advent of radio. It was now possible for the operator of a radio station or radio network to play someone’s music for audiences which quickly went from hundreds to hundreds of thousands. At first the Federal Communications Commission frowned on such stations playing pre-recorded music, and so music was mostly live concerts–but often such live concerts were also recorded and replayed later, so it was becoming a moot point. Now a musician could be heard by many people from the sale of a single record–but the sale of a single record would never support the artist for even one day, and he could not produce enough records in a day to do that. It was agreed that a radio station who played a recording by an artist owed that artist–and indeed, also owed the composer and the publisher–royalties under copyright law. However, as the number of radio stations burgeoned and the number of available recorded songs multiplied, that was going to be a prohibitive issue.

A solution was found. The American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers came into existence. Now a musician simply registered his recording with the society, and the society negotiated with radio stations to collect royalties for airplay of songs. The theory is that every time a radio station plays your song, you split a penny with several other people who also get paid (like your record company and, actually, A.S.C.A.P. itself). Of course, it was not then possible for anyone to count how many times every song was played on every radio station, but A.S.C.A.P. had a simple solution. Every week some sample group of radio stations–a different sample group each week–writes down every song it plays, and A.S.C.A.P. compiles these lists and extrapolates from them how many times each song was played on all radio stations in the nation. Every radio station then pays a license fee to A.S.C.A.P. (there are numerous factors determining how much is paid, largely based on how many people are likely to hear it), and that money gets paid to the musicians.

The system has expanded over the years. Today churches who wish to sing songs that are not in their hymnals without buying sheet music for everyone buy a license to print or display songs for use in services, and the composers, authors, and sometimes performers of those songs are compensated from that. It certainly has been taxed by the development of file sharing and the Internet, but thus far it has managed to expand to meet the changing times.

I am going to suggest that it expand a bit more, or perhaps that it be imitated.

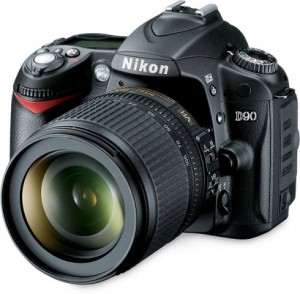

One of the problems on the Internet is that there are a lot of pictures–“images”, whether photos or computer drawings or scans of artwork–and that it is extremely simple to copy an image and use it somewhere else. For most of us, that’s not a big deal–what little artwork might be labeled mine is of meager quality. We would object to our personal photos being used in some corporate advertising campaign, but probably wouldn’t think twice about someone using something we drew somewhere else. In fact, we frequently post and repost probably thousands of images per day on Facebook, knowing that they are gone beyond our control and we will never be compensated for any work we invested in them. However, there are people who are dependent on being able to sell their images–photographers, artists, animators–and when we “steal” their work we are robbing them. Often, though, we have no way of knowing whether any particular image we encounter is free to use as is, free to use in other ways, or something that requires the purchase of a license.

It might be argued that in a world in which everyone carries a digital camera in his pocket there is no longer a place or a need for professional photographers. When was the last wedding you attended at which “a friend of the bride” did not shoot the pictures? Photographers may be a profession of the past.

That is not necessarily true. We do not get many photos from tourists visiting war zones, or admitted to peace talks or legislative sessions; for these, at least, we need professionals. We probably need them for many other things. If, though, we do not compensate them (not to mention others in the visual arts) for their work, they will be forced to cease doing it. Yet it is a simple thing, a small thing, to use an image that you find floating out there on the web and float it a bit further, without any notion of its origin. Is there a solution for this?

Certainly it is possible for photographers, artists, animators, and filmmakers to surf the web seeking their stolen images, and sue any offending web site; however, absent some clear indication that the thief was aware of the ownership status of the image, United States law only allows for an order to remove the image from the site. Something more is needed for compensation. Yet the tools all exist to launch something like A.S.C.A.P. for artists and photographers. We already have systems monitoring traffic to various sites, so we know how heavily any site is visited. We have “spiders” crawling the web, and Google has demonstrated the ability to identify images by subject matter. Digital signatures can be implanted in images that alter nothing visible but make the image recognizable to such a spider. Let’s let people who create such images sign their work digitally. Then every company that provides web site hosting space can be required to buy a license on behalf of those whose sites are hosted on its servers, price based on server size and traffic volume, costs to be passed to those who build the sites. Then if you happen to use a photo from an Associated Press photographer, or an image from an unfamiliar artist, or any other work on which someone holds rights, the system will count it and tell A.S.C.A.P. to compensate the owner.

It works for registered songs on the radio; why not for images?

I have previously written on copyright law, including Freedom of Expression: Copyright and Intellectual Property.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Please note that this form contacts the author by e-mail; for comments on the site, see below’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]